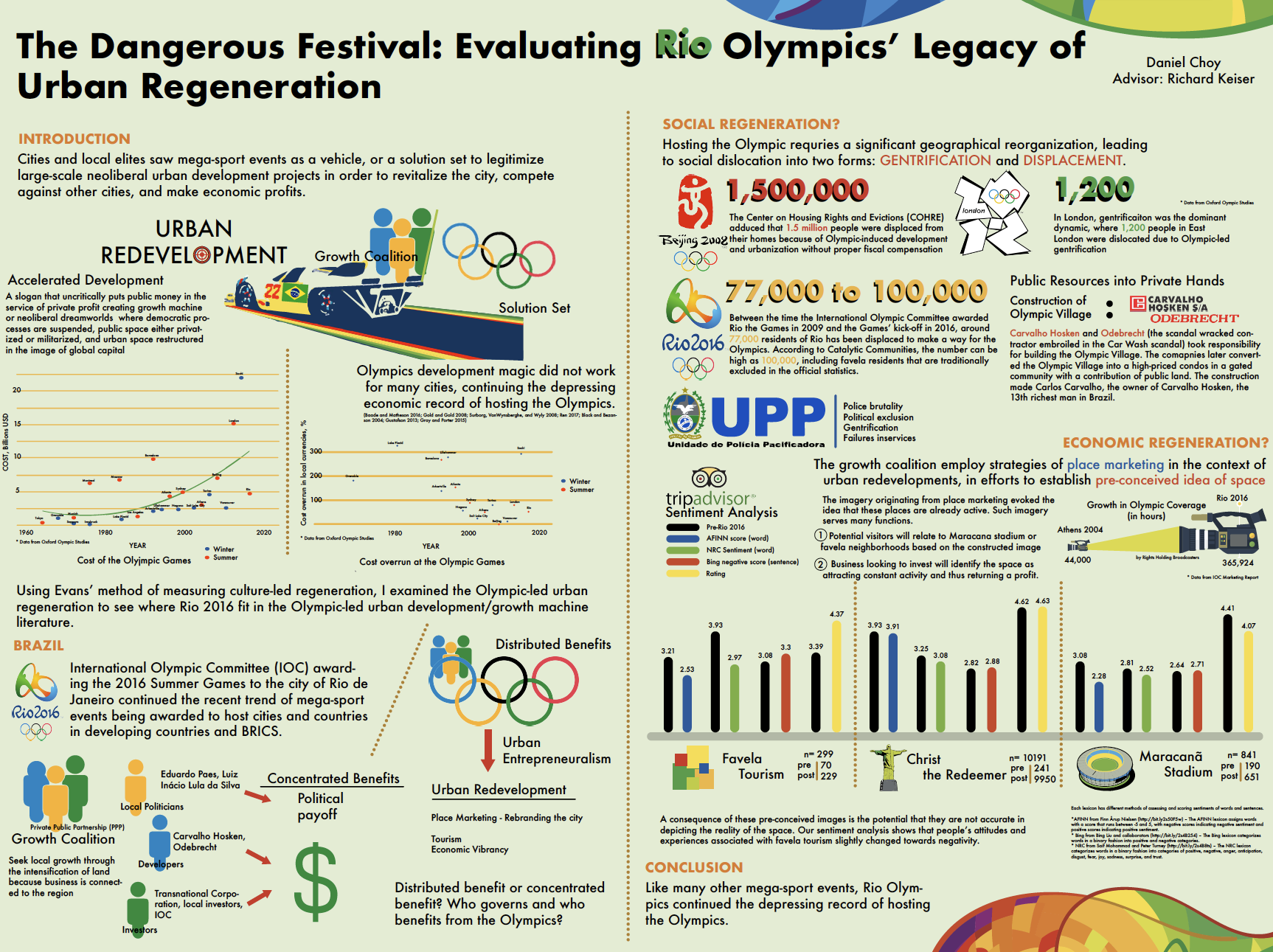

An infographic that explains the summary of the paper

The announcement made in 2009 in Copenhagen, Denmark, that Rio de Janeiro will host the 31st Olympiad excited Brazilians. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the President of Brazil at that time who had been the driving force behind the bid for years with his strong personal and vocal commitment wept uncontrollably after the announcement. “Brazil went from a second-class country to a first-class country, and today we began to receive the respect we deserve,” Lula da Silva said after the announcement. “Can you imagine how many Argentines, Uruguayans, Paraguayans and Peruvians will go to Brazil? It is not only a Rio Olympics, it is Brazil’s Olympics” (Fonseca 2009).

Brazil’s successful bid to host the two most popular mega-sport events, FIFA World Cup in 2014 and the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro in 2016, were regarded as important opportunities for financial benefits, global media coverage, and place marketing. Hosting mega-sport events has become an important element in the orientation of nations to become an international or global society (Horne and Manzenreiter 2006). In the case of the Olympics, ever since the mega-sport event has been telecasted internationally , the world festival has become a stage for cities and countries to present their achievements and prides to viewers and the media (Rohde 2018). In Brazil, authorities were excited to capitalize on this global attention in order to boost exports, attract tourists, increase political influence, and legitimize urban redevelopment projects.

It is not new in the literature that mega-sport events function as a vehicle to legitimize urban redevelopment projects in urban areas. It is also not new in the literature that hosting mega-sport events involve some of the most expensive, complex, and controversial urban redevelopment and regeneration projects that cities and nations undertake (Baade and Matheson 2016; Gold and Gold 2008; Surborg, VanWynsberghe, and Wyly 2008; Ren 2017; Black and Bezanson 2004; Gustafson 2013; Gray and Porter 2015). In this thesis, I incorporate aspects of different literatures on urban governance and urban political economy. I specifically cover literatures on growth machines, entrepreneurial city, revanchism, and globalization to explore one of the most recent globalized urban spectacles, the Summer Rio Olympic Games. Although there have been studies on the varied motivations for staging Olympic Games and the outcomes in terms of urban redevelopment, there are not many studies that examine the Olympic-led urban regeneration in Rio. By discussing the above literatures and using Evans’ method of measuring culture-led regeneration (Evans 2005), I will examine the Olympic-led urban regeneration and the Olympic legacy in Rio. The article is divided into five main sections followed by a conclusion. Following the introduction, we trace and review the literatures on urban regimes, growth machines, entrepreneurial city, and how these literatures are connected to the rise of Olympic-led urban regeneration. Based on the discussion in the first section, the second section briefly explores the background of Brazil and the rationale behind hosting both the World Cup and the Olympics. The third and fourth section will assess whether culture-led regeneration is evident in Rio by looking at several case studies. The fifth section will review the possibility of economic regeneration by analyzing Rio Olympics’ place marketing strategy through sentiment analysis.